Land use planning is transforming our living environments. Our experts dissect the issues raised by current events and share the news and ideas that make us progress together.

Réflexions BC2

Is the shopping centre a model in need of reinvention?

Chapters

Introduction

The original large-scale retail space model no longer serves the market’s current dynamics: the transition towards more urban complexes, the increased preponderance of online commerce, the search for new “experiences”, the optimization of land according to real estate pressure and the ageing of many centres make it necessary to redefine existing models.

Redefining the shopping centre model is inevitable and comes with many challenges. However, it also provides an opportunity for urban planners, architects, and developers to create new mixed-use environments and consider the densification of these spaces.

The story of a successful model

The literal French translation of the term “mall” is “mail”, Old French for “alley” or “promenade”.

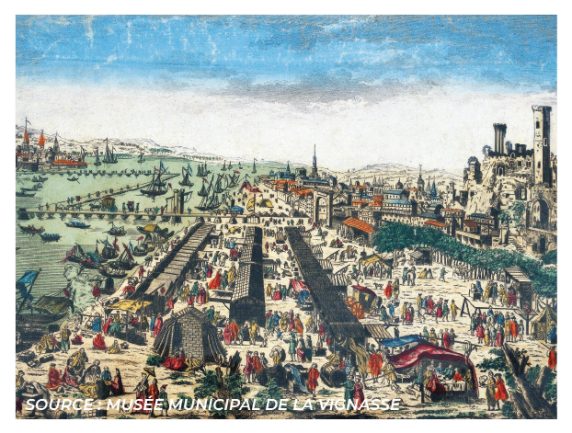

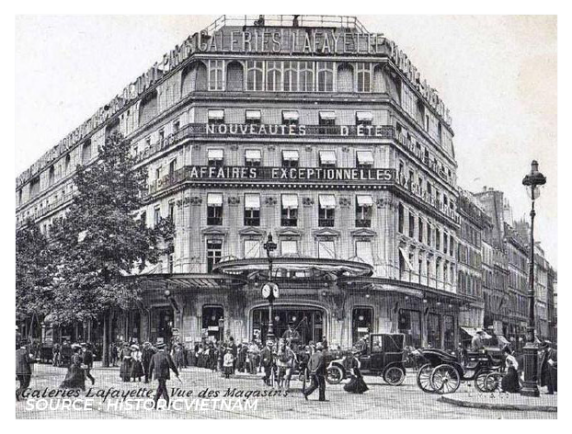

This etymology underlines the very origin of the principle of the shopping centre, whose design was inspired by the first public markets and bazaars of Antiquity, the fairs and covered markets of the Middle Ages, and then by the appearance of shops, shopping streets, covered passageways, covered market halls and the first department stores during the industrial revolution in the 19th century. The aim was to offer shoppers an attractive place to shop, walk around sheltered from the weather, in a place with a wide variety of stores featuring large windows to encourage the visitor to enter and, above all, stay and consume.

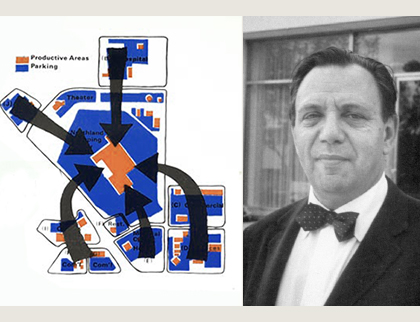

The creator of the model

The Austrian-born American architect Victor Gruen is credited with pioneering the regional shopping centre model. Having popularized many retail innovations, he designed the first suburban indoor shopping centre with an artificial atmosphere, the Southdale Centre (Minnesota), in 1956. Originally conceived as a satellite to the downtown centre, forming a community hub with a mix of functions, the model was replicated in multiple North American and European cities.

Gruen’s original idea was to offer an urban experience, with an emphasis on the design of common spaces, furniture, planting, and entertainment. However, as the model expanded, in most cases, only the commercial function was retained. As early as the 1960s, Gruen took a critical look at the duplication of the model, deploring the lack of consideration for the quality of the spaces, the treatment of the facades and the ‘asphalt desert’ surrounding them.1

Southdale Centre in Minnesota

Source : Victore Gruen, conference « The Shape of Things to Come », 1968

Changes in commercial typologies2

Markets located in major ports (e.g., Piraeus; Byblos; Tyre; Cyprus).

The rise of stores and covered passages in the 19th century. The passages have long glass canopies offering better lighting, a place to stroll and shelter comfortably from bad weather.

Neighbourhood shopping centres located along major arteries, located at the back of the lot with a large space dedicated to parking at the front, e.g., Place Côte-Vertu.

Large shores in stand-alone buildings (big-box stores) with low-tech architecture and facing large, shared parking lots, e.g., Marché Central in Montreal; Carrefour de la Rive-Sud in Boucherville.

5. First bazaars in the East in the 4th century (Constantinople; Cairo): alleys with stalls, sheltered from the weather and of a certain height to let in light. European fairs from the 11th century onwards: the meeting point of various nations in a large commercial area that had not yet been settled.

Innovative new look for department stores: a large surface area, a wide variety of products, low fixed prices, free access to products and large windows used for advertising!

Shopping centres with one or two large shores as the “locomotive”, connected by an internal pedestrian walkway giving access to smaller specialized shops. The central square becomes a focal point. Centrally located, the shopping centre is surrounded by large parking areas, e.g., Galeries d'Anjou; Carrefour Laval.

A commercial offering complemented by other functions (offices, restaurants, hotels, theatres, cinemas) to deliver a complete “experience” day or night. The development follows the original model of the outdoor commercial street but in a privately managed space, e.g., Quartier DIX30 in Brossard; Don Mills in Toronto.

The ageing of the model

For many years now, the original shopping centre model has been slowly fading away as consumer buying patterns change and as buildings reach the end of their useful life. The shopping experience is no longer just about what you want. How people purchase is increasingly important; this requires rethinking the way products and services are offered. The COVID-19 pandemic only amplified this phenomenon as the population is more sedentary and less likely to shop in enclosed spaces. Moreover, the ageing of assets is prompting developers and managers to review their shopping centres, sometimes radically, by adapting to these new realities, seeking to optimize these operations as much as possible, even if this means joining forces with other developers or opening up to new activities, such as residential uses.

Structural factors

Ageing real estate assets

Those buildings erected between the 1950s and 1970s struggle to withstand further renovations and are often demolished and rebuilt from scratch.

The need to bring things up to standard

The key challenge for such assets is maintaining a safe and up-to-date sales and service location, which is difficult to do with old buildings.

Business model obsolescence

The very shape and size of establishments is changing based on the needs of the clientele; therefore, operators must reinvent themselves and change the traditional model by:

- Reconnecting businesses with their communities.

- Diversifying the offer to increase customer retention.

- Favouring more compact establishments set closer to each other to increase the proximity of supply.

- Developing sustainable and innovative strategies.

- Where appropriate, integrating other urban functions to make the real estate operations that such changes entail profitable.

Cyclical factors

Demographic and socio-cultural changes

Slower population growth, an ageing population, and a plurality of cultural communities are all having an impact on commercial demand.

The rise of e-commerce

Consumption patterns have diversified. Between 2009 and 2022, the share of Quebec adults who made an online purchase increased from 20% to 75%.3 The value of online purchases has also increased, with a significant increase during the COVID-19 pandemic (+30% between 2019 and 2021). However, the easing of public health restrictions has also meant that consumers are returning to stores, leading to hybrid purchasing practices.4

Improving the customer experience

The development of new services in shopping centres is becoming an underlying trend (café, barber, hairdresser, tailor, etc.). However, one in two shoppers still browses in-store before buying online.

The rise of environmental concerns

The changing lifestyles of the younger generation and growing concerns for the environment are leading consumers to question the provenance of the products they buy or the environmental and ethical codes of conduct respected by the retailers and shopping centres they visit.

Proximity principle

In central urban areas, developments in recent years have favoured the proximity principle: the average size of branches has been reduced to increase the number of sales outlets in the area. This trend has been observed for Quebec pharmacies. The average surface area has halved, but the number of branches has increased to ensure local service.

Pharmacy surface area in Quebec

Lower parking ratios

Until the 2010s, commercial developments favoured high parking ratios. However, current developments, particularly in the urban core, show that large banners and municipalities are willing to reduce the number of parking spaces per square metre to ensure optimal land use.

Case studies

Ville Mont-Royal - Carré Lucerne

Redevelopment of a neighbourhood shopping centre

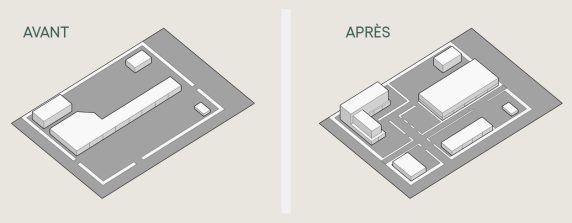

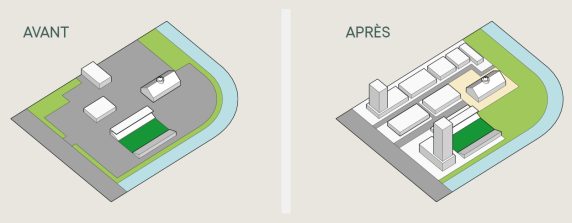

Lucerne Square was originally a classic commercial strip in Town Mount Royal, centred on a food market and local shops and services. It was made up of aligned stores located at the back of the lot, with ample parking in front.

The recent redevelopment project carried out by First Capital Realty, owner and manager of the centre, was to create a more consumer-friendly environment that is better integrated into its surroundings, taking into account the new standards: several buildings, mainly located on the site’s perimeter, to promote a better interface with the residential neighbourhood, some shops on two levels, part of the parking lot developed inside and the integration of the residential function, above certain commercial podiums.

Vancouver - The Amazing Brentwood

The reorganization of a regional shopping centre

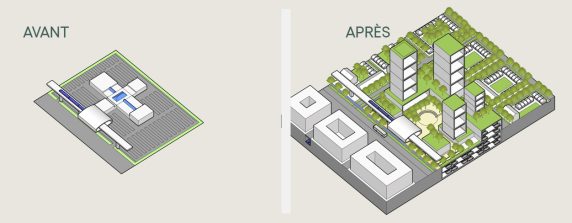

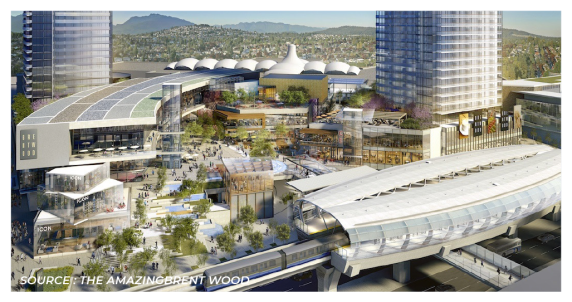

Dubbed the “Amazing Brentwood” by its developer, this shopping centre left the strip mall category behind for the mega mall. Located on an 11-hectare site in the Burnaby area of Vancouver, the mall was originally surrounded by thousands of surface parking spaces.

With the opening of the Brentwood SkyTrain station, which connects to the downtown core in 20 minutes, and the interest of the operators in completely revising the model, a vast urban requalification project is underway.

When completed, the site will house 11 residential towers with 6,000 condominiums and rental units in addition to 250 shops and restaurants, parks, a central plaza with a farmers’ market, seasonal and social events, planted boulevards, green roofs, etc.

Ottawa - Lansdowne

From underused site to mixed neighbourhood

Lansdowne Park was redeveloped on public infrastructures. The site, located within the historic district of “The Glebe”, between the Rideau Canal and a residential area, was used exclusively as a sports and event venue, with its stadium and the Aberdeen Pavilion, and included numerous outdoor parking lots.

The major redevelopment of Lansdowne was planned from 2012 onwards in public-private partnership mode. This new mixed-use neighbourhood combines several two-storey commercial buildings open to the street and connected by underground parking. The TD Stadium has been renovated, and the Aberdeen Pavilion has been converted into a farmers’ market. A skating rink is set up in winter, and a large park has replaced the asphalted surfaces.

The shopping centre as a “third place”

The shopping centres redeveloped in recent years has an ever-wider range of functions: community, institutional, health, sports and leisure services, entertainment, and residential units (including residences for the elderly). The diversification of urban functions5 is accompanied by new forms of sociability. This phenomenon is analyzed through the concept of the “third place”.

In addition to the home space (first place) and the workplace (second place), individuals need to frequent spaces that encourage meetings and sociability, i.e. the “third place”. Shopping centres embody this function for certain groups, such as the elderly and young people.7

Assess to better transform

SEVERAL CRITERIA CAN BE CONSIDERED TO IDENTIFY AND CHARACTERIZE LARGE COMMERCIAL SPACES THAT ARE SUBJECT TO A REDEVELOPMENT AND DENSIFICATION STRATEGY:

Criteria relating to commercial hubs include the centre’s construction period, the current commercial mix and its recent evolution, the surface area devoted to parking, the scale of renovation or not of the centre, the existence of clauses in big banner leases that impose constraints on redevelopment and densification, the configuration of the centre and the location of vacant premises, among other things.

Criteria relating to the insertion environment, such as the site and location, current and future accessibility, proximity to a structuring public transport mode, the urban environment, the urban fabric, the supply of surrounding services (private, public, and community), the presence of new developments in the vicinity (development pressures), etc.

Focus on geomatics

Geomatics can be a powerful tool for targeting and prioritizing commercial hub redevelopment interventions. It makes it possible to visualize and spatially cross-reference layers of information from various databases to perform multi-criteria analyses. For instance, some municipalities publish data on sites with high redevelopment potential. By combining this data with zoning, public transport hub or census data, it is possible to filter the information to identify sites that meet a specific set of criteria.

THIS FICTITIOUS CASE STUDY ILLUSTRATES ONE OF THE MANY USES OF GEOMATICS: BY CROSS-REFERENCING DATA ON ZONING, POPULATION GROWTH AND PROXIMITY TO PUBLIC TRANSPORT, IT IS POSSIBLE TO IDENTIFY, IN A GIVEN TERRITORY, COMMERCIAL SPACES THAT WOULD BENEFIT FROM AN ENVIRONMENT CONDUCIVE TO A REDEVELOPMENT STRATEGY.

Conversion challenges

REDEVELOPING A SHOPPING CENTRE MOST OFTEN REQUIRES REGULATORY CHANGES IN TERMS OF HEIGHT, DENSITY OR ADDITIONAL FUNCTIONS.

Whether it’s a change of zoning or a specific project, several approval stages and the support of various stakeholders (civil servants, elected officials and citizens) are required. The process often leads to revisions to the initial project – if not to an outright change of course – depending on the comments and issues raised (businesses that need to remain open, phasing, social acceptability, etc.).

Reinventing the model

Governance

With the participation of various stakeholders: inclusion of affordable housing, better sharing of public and private spaces, urban sustainability, etc.

Environment

Better upstream site, rainwater and waste management, user-friendly outdoor spaces, use of renewable energy or materials, reuse of existing buildings

Mixed use, density, and compactness

Mixed spaces where people can work, live, and relax: housing, offices, hotels, leisure facilities, culture and education, coworking, etc.

Technologies

Consumer behaviour, interactive fitting rooms, drone deliveries, management of pedestrian and vehicle traffic flows, etc.

Experience and eating

Meeting places, day and evening entertainment, rides, skating rinks, climbing walls, children's games, street food trucks or a major restaurant hub featuring fresh produce, cooking classes, delivery, etc.

Proximity scale

Setup in central urban areas or near major transport routes, smaller store size and parking ratios, tiered or underground parking, street alignment and entertainment, etc.

Redefining space for pedestrians

Bringing the buildings closer to the street, no blind walls, and more user-friendly and safe traffic lanes for pedestrians, cyclists, or people with reduced mobility

Flexibility

More spontaneity and originality, temporary shores, seasonal pop-ups, flexible leases, shared warehouses, etc.

Large discount stores or quality boutiques

For more details

CHIVALLON Christine et al., Artefact de lieu et urbanité, le centre commercial interrogé, In: Les Annales de la recherche urbaine, N°78, 1998. Echanges / Surfaces. pp. 28-37

HARDWICK, Jeffrey. Mall Maker – Victor Gruen: Architect of an American Dream, 2010, 288 pages.

MAUMI Catherine, L’urbanisme tri-dimensionnel de Victor Gruen à l’épreuve du « futur prévisible » des villes nouvelles parisiennes, Inventer le Grand Paris, 2015.a>

NEDELEC Pol-Alain, Le Centre Commercial – histoire d’une forme, portée d’un modèle, 2014, 145 pages.

TAILLON Grégory, Et si les centres commerciaux devenaient de véritables quartiers?, Kollectif.net, 2017.>

CHIVALLON Christine et al., Artefact de lieu et urbanité, le centre commercial interrogé, In: Les Annales de la recherche urbaine, N°78, 1998. Echanges / Surfaces. pp. 28-37

HARDWICK, Jeffrey. Mall Maker – Victor Gruen: Architect of an American Dream, 2010, 288 pages.

MAUMI Catherine, L’urbanisme tri-dimensionnel de Victor Gruen à l’épreuve du « futur prévisible » des villes nouvelles parisiennes, Inventer le Grand Paris, 2015.a>

NEDELEC Pol-Alain, Le Centre Commercial – histoire d’une forme, portée d’un modèle, 2014, 145 pages.

TAILLON Grégory, Et si les centres commerciaux devenaient de véritables quartiers?, Kollectif.net, 2017.>

Notes

- Gruen, Victor (1964). The Heart of Our Cities, 368 p.

- De Moncan, Patrice (2008). Histoire des centres commerciaux en France, 331 p.

- Académie de la transformation numérique (2022, June 18). Le commerce électronique. https://transformation-numerique.ulaval.ca/enquetes-et-mesures/netendances/2022-03-le-commerce-electronique

- Académie de la transformation numérique (2022, August 12). Le commerce électronique. https://transformation-numerique.ulaval.ca/enquetes-et-mesures/netendances/2022-03-le-commerce-electronique#:~:text=%C3%89volution%20du%20montant%20des%20achats,a%20augment%C3%A9%20comparativement%20%C3%A0%202020

- CBC (2017, September 3). Les défis des centres commerciaux. Radio Canada https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1053798/magasinage-centre-commerciaux-ere-numerique-en-ligne-transformation

- Oldenburg, Ray (1989). The Great Good Place, 384 p.

- Besozzi, T. (2018). The daily sociability of elderly people in a shopping center: a peculiar leisure, Bulletin de l’association de géographes français, vol95(1)

- Gruen, Victor (1964). The Heart of Our Cities, 368 p.

- De Moncan, Patrice (2008). Histoire des centres commerciaux en France, 331 p.

- Académie de la transformation numérique (2022, June 18). Le commerce électronique. https://transformation-numerique.ulaval.ca/enquetes-et-mesures/netendances/2022-03-le-commerce-electronique

- Académie de la transformation numérique (2022, August 12). Le commerce électronique. https://transformation-numerique.ulaval.ca/enquetes-et-mesures/netendances/2022-03-le-commerce-electronique#:~:text=%C3%89volution%20du%20montant%20des%20achats,a%20augment%C3%A9%20comparativement%20%C3%A0%202020

- CBC (2017, September 3). Les défis des centres commerciaux. Radio Canada https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1053798/magasinage-centre-commerciaux-ere-numerique-en-ligne-transformation

- Oldenburg, Ray (1989). The Great Good Place, 384 p.

- Besozzi, T. (2018). The daily sociability of elderly people in a shopping center: a peculiar leisure, Bulletin de l’association de géographes français, vol95(1)